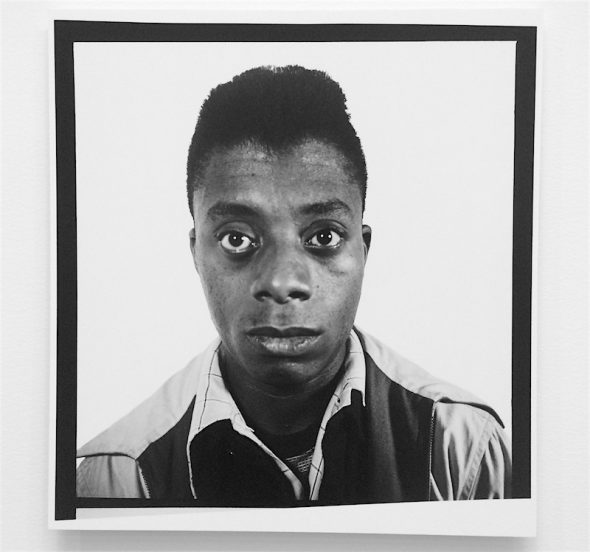

James Baldwin at David Zwirner

I have written previously about the James Baldwin retrospective I produced and directed at Lincoln Center for PEN American Center; I’ve also written about the particular pleasure, at once nerve-racking and gratifying, of working with the New Yorker critic Hilton Als on that show. (You can read the speech Hilton Als gave at my Lincoln Center event here.) But now Hilton has curated an exhibit at David Zwirner Gallery in New York titled God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin that makes a similar attempt to understand Baldwin as a figure in the round, this time with even more of an emphasis on the visual arts than we had from the stage at Lincoln Center.

James Baldwin would seem to make a rich subject for such an exploration because, in addition to the various poor/gay/black identities that have long preoccupied Hilton Als, he was friends and intimates with a great many visual artists, first among them the pioneering African-American painter Beauford Delaney. A number of Delaney paintings are included in this exhibit, as well as photographs by Baldwin’s schoolmate Richard Avedon. The problem is that I, at least, wasn’t sure what their inclusion revealed about Baldwin that is not more readily apprehended by reading just about anything he has ever written. These artists had their own creative interests: where Baldwin appears as subject, as in a series of sketches of writers, it appears incidental; where he does not and the works just address similar themes, as in the contemporary installations by Kara Walker and others in an adjoining gallery, it seems a chance meeting in a big world. I appreciated hearing Baldwin himself sing “Oh, Precious Lord” in his warm, sonorous, mournful voice — a vinyl record player was set up in one corner of the main gallery — but I give Hilton no credit for that: we closed the show at Lincoln Center with that song.

The simple truth is that Baldwin is bigger and more compelling than this show. He was regarded by many, in the early-1960s, as an incendiary truth-teller on the subject of race in America and then, by the 1970s, as hopelessly conciliatory in his stance toward white America. In fact, he didn’t much change; it was the world that changed around him. And now it has changed again and Baldwin seems almost uniquely relevant once more. Hilton Als is trying to make a case for that in this exhibit but he approaches Baldwin too narrowly, looking at him through the prism of his body and all the identities embedded in it. So we hear his stepfather’s heartbreaking observation that young Jimmy was “the ugliest boy he’d ever seen,” to which the title of the exhibit is meant to serve as a rejoinder. We read his letters to the white grade school teacher, Orilla Miller, who nurtured his talents at a time when few others in his life were willing to, but I learned much more from the terrific Raoul Peck film “I Am Not Your Negro” about how this relationship made it hard for Baldwin to hate white people though, as he acknowledges, he did try. Hilton has always seemed to treat Baldwin as first and foremost a gay writer — he criticized the Baldwin estate from the stage at Lincoln Center for supposedly sweeping his homosexuality under the rug — or, perhaps, first black and then gay. But Baldwin himself, though he wrote his ‘coming out’ novel Giovanni’s Room early on, did not publicly assert his sexual identity until the very end of his life. That seems fair enough: he had much else to say, on many other subjects, and he wanted to focus on those. What makes Baldwin especially relevant today, I submit, is that much like Obama he understood white people well enough to tell them some very pointed and difficult truths in a way that they would hear, and consider, and perhaps accept. That is not the only stance a black writer (or politician) can take, but it is a valuable one if you believe, as Baldwin did, that the so-called black problem is really a white problem. The Trump era, whatever else it might achieve, certainly provides fresh reasons to consider the wisdom of that insight.

~

As a bonus, for anyone going to the David Zwirner Gallery on W. 19th St be sure to walk five blocks north to Marianne Boesky on W. 24th St and see the breathtaking Paul Stephen Benjamin exhibit Pure, Very, New. In particular, go straight to the rear wall of the gallery and stare at the nine large black squares — called Flow, from 2017 — for as long as you have time to do so: slowly your eyes will adjust to the nearly uniform darkness of the surfaces and portraits of black males will emerge. They are photographs, in fact, though you will have to peer very closely for a very long time to see this. They are also a kind of magic.